One of the first civil engineering undertakings that Benjamin Outram (1764-1805) was involved with was the Cromford Canal in Derbyshire. This was to run from the head of the Erewash Canal at Langley Mill by way of Ripley to Cromford with a branch to Pinxton. The Act permitting its construction was passed in 1789 and construction work commenced straightway. In Aug 1789 the canal company appointed William Jessop as their Consulting Engineer and Benjamin Outram as their Superintendent at a salary of £200 per annum. Work on this canal did not proceed too well. Two major aqueducts, the Amber and the Derwent, partially failed and the original contractors withdrew before the canal was completed. These were Thomas Dadford and Thomas Sheasby but by Jan 1791 they had become insolvent and from this point onwards Outram managed the works until the Cromford Canal was opened throughout in 1794. The only trouble-free achievement was the 2,966-yard-long Butterley tunnel, at that time the third longest in the country, for which Outram was responsible.

On the 5 Sep 1793 Outram placed an advertisement in the Derby Mercury for the sale of surplus equipment at Butterley Hall, ‘···· lately used in executing the Works of the Cromford Canal.’

Among the items to be sold were:

Miners’ Waggons. Waggon Rails. A good Machine with 6 Waggons and Rails, for raising Earth out of deep Cutting.

It is almost certain that these items refer to temporary tramway systems used for the removal of spoil during excavation of Butterley Tunnel and its approach cuttings. These represent an early record of Outram’s involvement with railed transport. Although the method of construction is unknown it is likely that they were waggonways, similar to those used in coal mines, using either wooden rails or wooden rails covered with thin sheathing or ‘plating’ of iron to improve their wear resistance, hence the term ‘plateway’.

In Jun 1790 Francis Marcus Beresford, a local landowner and attorney to the Cromford Canal Company, purchased the Butterley Hall Estate adjoining the Cromford Canal. Around this time Benjamin Outram and Company was founded by Benjamin Outram, William Jessop (1745-1814), Francis Beresford (1737-1801) and John Wright. William Jessop was a civil engineer and John Wright was the grandson of Ichabod Wright a Nottingham banker and son-in-law of Francis Beresford. The company works was known as the Butterley Ironworks and this was located at Butterley, Ripley, Derbyshire. After the deaths of Francis Beresford and Benjamin Outram the company was carried on by John Wright, Margaret Outram (widow of Benjamin) and William Jessop, and in 1807 it was renamed the Butterley Company.

The estate was rich in deposits of ironstone and coal and the company immediately began to make use them. In 1791 and 1792 Francis Beresford purchased land around the nearby village of Crich in order to open a limestone quarry. In 1793 Outram connected this quarry to the Cromford Canal at Bullbridge Wharf by means of a tramway a little over a mile in length and having a gauge of 3 feet 6 inches. Waggons and L-section rails for this were manufactured at the Butterley Ironworks.

Leawood Pump House, Cromford Canal. View looking NW towards Cromford from the Leawood Aqueduct. The pump house is located beside the canal on the right bank of the river Derwent. It opened in 1849 to pump water from the river Derwent into the canal when the water level was low. It uses a Watt-type beam engine capable of raising water up to a height of 30 feet and discharging it into the canal. The 70hp beam engine was designed and erected by Graham and Company of Milton Iron Works, Elsecar, Yorkshire, at a cost of £1,965. The beam length is 33 feet, the piston diameter is 50 inches, the stroke is 10 feet and the engine works at seven strokes per minute. The pump house is listed Grade II*, List Entry No. 1247889, with the name ‘High Peak Pump House’. |

|

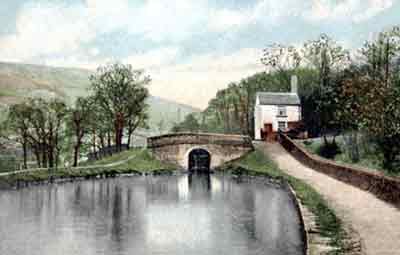

Leawood Aqueduct and Pump House, Cromford Canal, early 20th century. View looking north over the Derwent Valley. The entrance to the Lea Wood or Nightingale Branch Canal is on the far side of the canal to the right of the aqueduct. This 550-yard long branch to Lea Wood Wharves was built in 1802 by Peter Nightingale, the great uncle of Florence Nightingale. The hamlet of Lea Wood can be seen in the background. |

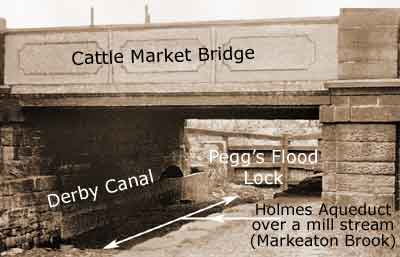

The broad Derby Canal was promoted in 1792 and it was 14½-miles long, the original scheme having been drawn up by Outram. It commenced at Sandiacre, by a junction with the Erewash Canal, and proceeded by Borrowash and Spondon to Derby, where there were junctions with the 3-mile long Little Eaton Branch Canal and a short branch to the upper reach of the river Derwent in the city. It crossed the Derwent on the level and continued by Osmaston to Swarkeston, where it joined the Trent and Mersey Canal.

The canal was significant for Holmes Aqueduct, which was built to facilitate barges crossing the river Derwent along the top of a weir built to control the level of the water in the river.

Weir and Long Bridge across the river Derwent, Derby, looking south, early 20th century.

The Derby Canal crossed the river on the level between Pegg’s Flood Lock on the south bank and White Bear Lock on the north bank. Barges were hauled along the top of the weir on the upstream side of Long Bridge.

Before he could accomplish this crossing, Outram first had to build an aqueduct over a mill stream (Markeaton Brook) with limited headroom below it. At that time, the normal practice would have been to build a stone aqueduct supported by an arch but this was impossible because of the limited headroom and Outram's solution was to build an iron aqueduct.

In order to achieve this Outram designed a prefabricated cast-iron trough and, although no records have survived, it is likely that the components for this were produced at his own ironworks, that is, Benjamin Outram & Co (aka the Butterley Co) at Ripley, Derbyshire. Stone abutments were built on each side of the mill stream and the trough was assembled so that the ends rested on the abutments. Holmes Aqueduct, the world's first navigable cast-iron aqueduct, was filled with water in Feb 1796 and it predates Thomas Telford's Longdon-on-Tern Aqueduct by one month.

It is understood that in section the trough was 44 feet long x 15 feet 6 inches wide x 5 feet 8 inches deep. The two sides and base were each fabricated from four cast-iron plates, 1¼ inch thick, that were flanged to enable them to be bolted together and braced in order to withstand water pressure. The side plates represented voussoirs used in the construction of traditional stone arches.

Soon after Holmes Aqueduct came into use it was apparent that it was under designed and on several occasions, up until 1930, remedial work was needed to keep it functioning. Nonetheless, it survived until 1971 when it was demolished to make way for a city-centre development scheme. No attempt was made to save this important structure, nor was an archaeological survey undertaken or a photographic record made. In this manner, the world lost its first cast-iron aqueduct.

In 1793 work began on the Little Eaton Gangway (sometimes known as the Derby Canal Gangway) that was a tramway extension of the Little Eaton Branch of the Derby Canal. Outram was not initially involved with this as the line was proposed by William Jessop in a report dated the 3 Nov 1792. The first batch of L-section rails was ordered from Joseph Butler in 1793. However, it was completed under Outram's supervision in May 1795.

The tramway commenced at Little Eaton and it was 4-miles long leading to Kilbourne and Denby. Initially, it was built as a single track with passing places and the gauge was 3 feet 6 inches.

The Act for the Nutbrook Canal was passed in 1793 and it was primarily built to serve collieries at West Hallam and Shipley, Derbyshire. Outram was appointed as the Consulting Engineer and it was completed in 1796. It was a broad canal that started on the Erewash Canal just above Junction (or Stanton) Lock, Whitehouse, north of Sandiacre. It was 4½-miles long and it rose through 13 locks. The canal passed by Stanton Ironworks and then proceeded via Kirk Hallam and Nutbrook Colliery to end at Shipley Wharf.

Nutbrook Canal, early 20th century.

View looking NNE at Straw’s (or Moor’s) Bridge that carries High Lane East (A609) over the canal. Lock 7 (Straw’s Lock) is just visible through the bridge hole. Just before the bridge on the left is the site of the entrance to the former Hunloke Branch Canal which accessed collieries in the vicinity of West Hallam belonging to the Hunloke family of Wingerworth Hall, near Chesterfield, Derbyshire.

Although work on the narrow Ashton Canal (known as the Manchester, Ashton-under-Lyne, Oldham and Stockport Canal) started in 1792, it was not until mid-1798 that the canal company appointed Outram as their Consulting Engineer. It is likely that he had been working in some capacity, possibly as a contractor, on the construction of this canal from the outset but the company finally decided to formalise his position 'in order to better bring about its completion'. The reason for his late appointment is unknown but it is known that at an earlier stage the company advertised for a Consulting Engineer but no-one was appointed.

It appears that the opening dates for the Ashton Canal, including its branches, were not recorded. The main line opened in mid-1796 and the Doncaster Journal and Yorkshire Advertiser, for the 4 Feb 1797, stated that 'a canal conveyance was opened a few days ago between Stockport and Manchester, there has been one to Ashton for some months'.

An interesting fact about the Ashton Canal, and a possible reason for there being no specific opening dates, is that its main line was only 6.7-miles long whereas the length of the branches added together amounted to some 10½ miles. Had the Beat Bank Branch not been abandoned before completion then the branches would have been even longer. The shortest branch was the Islington Branch in Ancoats, Manchester, which was just over ½-mile long. Additionally, there were several private branches of which the Bradford and Clayton branches were the most prominent.

The Ashton Canal was of vital importance to the adjoining Peak Forest Canal Company as it gave access to Manchester. Though the two canals were initially independently owned, the management of both companies recognised that they had to cooperate with each other. Its line was from the intended Rochdale Canal at Piccadilly, Manchester, through Droylsden and Fairfield, then on to the Tame aqueduct in Ashton-under-Lyne and finally on to Whitelands to make a head-on junction with the Huddersfield Narrow Canal.

Four of the aqueducts on the Ashton Canal and its branches are notable, these being:

Store Street Aqueduct over Shooters Brook at Piccadilly, Manchester. Tame Aqueduct, which carries a short spur of the Ashton Canal over the river Tame to make a head-on connection with the Peak Forest Canal at Dukinfield. Waterhouses Aqueduct over the river Medlock at Daisy Nook on the Hollinwood Branch Canal. Crime Aqueduct over Crime Lane, near Daisy Nook, on the Hollinwood Branch Canal.

In 1793 Thomas Brown of Manchester and Disley surveyed, for some interested parties, the line of a narrow canal from the proposed Ashton Canal at Dukinfield via Hyde and Marple to Chapel Milton and thence by a 'Railway or Stone Road' to the limestone quarries at Loads Knowle near Dove Holes. The key figure in the Company of Proprietors of the Peak Forest Canal, as the parties became known, was Samuel Oldknow who was an industrialist based at Mellor and Marple. Among his many business interests were Mellor Mill and Marple Lime Works. The Act authorising the Peak Forest Canal was passed on the 28 Mar 1794.

An authorised share capital of £90,000 was to be raised in £100 shares with the ability to borrow another £60,000 when this became necessary. Initially only £80,600 was raised. The Act became effective on the 20 May 1794 and the canal company appointed Benjamin Outram and Thomas Brown as their Consulting Engineer and Resident Engineer respectively and they were jointly responsible for the construction of both the canal and tramway. Work on cutting the canal and constructing the tramway began almost immediately and cast-iron rails for the tramway were ordered from Benjamin Outram & Company at Butterley, Derbyshire, as early as Dec 1794.

As originally planned, the canal was to have been carried up a flight of locks between Bugsworth and the proposed terminal basin at Chapel Milton. These locks would have required a reservoir near the village of Wash to supply them with water and the land for this reservoir, across Hockham Brook, was actually purchased under the original Act. In spite of this, both Outram and Brown advised against this proposal following a re-survey of the line and in its place they recommended to the Committee that the length of the tramway should be increased.

The reasoning behind their recommendation was quite sound. A flight of 10 to 12 locks (Whitehough locks) commencing at Bugsworth, would have been required to lift the canal up to the proposed summit pound at Chapel Milton. This pound would have been fairly short and it was to have been supplied with water from Wash reservoir. Ideally, a summit pound should be as long as possible in order to store a supply of water itself and so supplement the reservoir. The pound at Chapel Milton would have been insufficiently long for this purpose and this meant that boats entering and leaving the basin at Chapel Milton would have caused an unacceptable loss of water through the locks and there was no guarantee that the reservoir could replenish this.

As a result the Committee decided in Jul 1795 to 'make the canal as far towards Chapel Milton as possible' on the level of the canal at Disley. Thus the canal was terminated at Bugsworth, 2 miles short of the proposed terminus at Chapel Milton. The canal was thus constructed 2 miles shorter and the tramway two miles longer than originally planned.

According to a report in the Derby Mercury, the upper level of the canal, between Marple top lock and Bugsworth, and the tramway, between Bugsworth and Loads Knowle, were simultaneously opened for trade on the 31 Aug 1796. The tramway included a tunnel at Stodhart, which is Britain's second oldest surviving railway tunnel, the oldest surviving one being Fritchley Tunnel, also in Derbyshire.

It is likely that the lower level of the canal was open by May 1798 when a temporary Marple Tramway, bypassing the locks, opened. Marple aqueduct was still incomplete and it may be that the tramway crossed the river Goyt on a temporary trestle bridge. The aqueduct opened on the 1 May 1800 and this is the generally accepted date for the opening of the Peak Forest Canal throughout with the exception of Marple locks. The construction of the locks was beset with financial problems as a result of which they were opened in stages. It is now believed that they opened right the way through somewhere between the first and twelfth day of Nov 1805.

In 1801 Outram resigned his post as the Consulting Engineer to the Peak Forest Canal Company in order to devote more time to Benjamin Outram & Company.

The Peak Forest Canal is 14¾-miles long and it rises through 16 locks at Marple. The Peak Forest Tramway was ultimately about 5¾-miles long.

In Apr 1794 the Huddersfield Canal Act was passed but subsequently the canal became known as the Huddersfield Narrow Canal to distinguish it from the Huddersfield Broad Canal (aka Sir John Ramsden's Canal). Shareholders in the Ashton Canal were the main promoters, which provided an alternative route to the Rochdale Canal over the Pennines. It commences in Huddersfield by a junction with the Huddersfield Broad Canal and proceeds by Golcar, Slaithwaite, Marsden, Diggle, Saddleworth, Mossley and Stalybridge to join the Ashton Canal at Whitelands in Ashton-under-Lyne.

Outram was appointed as the Consulting Engineer and because of the difficult terrain he was faced with huge problems, the greatest of which was the construction of the mighty Standedge Tunnel between Marsden and Diggle. He decided to only work on the construction of the tunnel from the two ends so as to save the expense of sinking very deep vertical shafts that would be needed to work at more headings but this extended the completion date. This idea was later rescinded with the aim of speeding up construction work.

The 20-miles long canal, with its 74 locks, was completed in 1798 with the exception of the tunnel, which was not completed until 1811, six years after Outram's death. Standedge Tunnel is Britain's longest canal tunnel. As built, it length was 5,456 yards but subsequently this was increased to 5,698 yards (3 miles 418 yards). It also the highest canal tunnel at 645 feet above sea level.

The Huddersfield Narrow Canal was sanctioned by an Act of Parliament (34 Geo III cap 53), which received the Royal Assent on the 4 Apr 1794. In addition to Benjamin Outram, others involved in its construction included Nicholas Brown (surveyor and superintendent), John Rooth (canal carrier and canal official), John Booth (engineer) and latterly Thomas Telford (engineer) who oversaw completion of the final section of Standedge Tunnel.

The first boat to navigate through the tunnel was on the 10 Dec 1810 and the official opening was on the 4 Apr 1811. There was no towpath in the tunnel, boats were legged through, and they could not pass. By the turn of the 20th century boats entered from the Marsden end at 6:00am, 2:00pm and 10.00pm and from the Diggle end at 2.00am, 10:00am and 6:00pm.

When the Huddersfield Narrow Canal was finally opened throughout in 1811 it became the third transPennine canal after the Leeds & Liverpool and Rochdale Canals. It was closed to navigation in 1944 and it reopened in May 2001.

Left: Stakes Aqueduct on the Huddersfield Narrow Canal.

Right: 19 Milestone incorporated in the parapet wall.

Stakes Aqueduct is the oldest surviving navigable cast-iron aqueduct and it is located over the river Tame at Stalybridge. It was built in c.1801 to replace Benjamin Outram’s original masonry four-arch aqueduct of 1795, which was destroyed in a flash flood on the 17 Aug 1799. It was designed by Benjamin Outram and prefabricated at his Butterley Ironworks.

It was erected from rectangular cast-iron sections bolted together. Each 3-foot wide section has a large tension flange, a small compression flange, and webbed side flanges. Each end section has stop-plank housings for maintenance purposes. The trough is about 21 yards long x 10 feet wide x 6 feet deep and the span over the river Tame is about 18 yards.

The masonry towpath bridge is hump backed with an elliptical arch and string course. Formerly, the parapet had round-topped coping stones.

Stakes Aqueduct and the adjoining towpath bridge are listed Grade II, List Entry No. 1356465.

Huddersfield Narrow Canal on the border of Millbrook and Mossley, early 20th century.

Lock 10W and lock house.

Huddersfield Narrow Canal at Slaithwaite, early 20th century.

View from lock 23E looking towards Britannia Road Bridge over the canal with the river Colne on the right. The mills in the background are, left to right, a saw mill, Globe Mills (woollen) and Bridge Street Mill (woollen).

In 1793 the business partners Joseph Outram (father of Benjamin) and William Jessop constructed a tramway to enable limestone from (Old) Hilts Quarry at Crich to be transported to the Cromford Canal at Bullbridge, where lime kilns were situated. The lime from the kilns was then transported by canal to the Butterley Company for use in iron making.

The tramway was owned by the Butterley Company (formerly Benjamin Outram & Company). It was single track, with a gauge of 3 feet 10 inches, and the cast-iron L-section rails were one yard long, secured to stone sleeper blocks with wrought-iron spikes. Initially, gangs of five waggons were worked by gravity and horses but in 1813 a walking steam locomotive (the Brunton Traveller or Steam Horse Locomotive) was introduced, this having been built by the Butterley Company. This was then withdrawn from service to be replaced by a small 0-2-0 industrial locomotive. Later, a Peckett 0-4-0ST locomotive was introduced. The Butterley Gangroad is also known as the Butterley Company’s Mineral Line, the Fritchley Mineral Line or the Critch Railway.

In Fritchley at the junction of Chapel Street, Bobbinmill Hill and Front Street, a tunnel, about 74-feet long by 10-feet high, was built under the road. As built, this was lined with masonry but later it was strengthened by the insertion of a short section of brick lining. This tunnel is the world's oldest railway tunnel.

Fritchley Tunnel.

This tunnel, now buried, is listed Grade II, List Entry No. 1422984.

The original quarry was abandoned in c.1850 and the (New) Hilts Quarry at Critch was opened a short distance away to the west. This caused the tramway to be re-aligned but the new quarry allowed the tramway to remain operational until 1933.

Fritchley Embankment with a Peckett 0-4-0T locomotive, Bobbinmill Hill, c.1930. This embankment was built in c.1850 when the original route was re-aligned and it has a gradient of 1 in 30 (3.3% or 1.91˚).

The sides and walls of the embankment are of coursed drystone construction with projecting through stones for strength and the walls are capped with edge-bedded coping stones. |

The 31-mile long Ashby Canal formed a connection between the Coventry Canal at Bedworth and the mining area of Moira in Leicestershire, situated to the west of Ashby-de-la-Zouch. Several tramways were constructed around Moira to connect collieries, limestone quarries and brick works to the Ashby Canal. The most noteworthy of these was the Ticknall Tramway, which connected limestone quarries and brick works to the canal at Willesley Basin.

In Aug 1798 the Ashby-de-la-Zouch Canal Company sought Outram's advice about a tramway to connect the northern end of their canal to local collieries and lime works. His proposal for the Ticknall Tramway was for lines to run from Cloud Hill (Breedon) and Ticknall joining at Ashby Old Parks Junction and then gradually descending through Ashby to the canal at Willesley Basin. The total length of this tramway was 12½ miles of which four miles were double track. The company accepted his report and appointed him as their Consulting Engineer. Work started in 1799, the rails and waggons being manufactured by Benjamin Outram & Company. The tramway was completed in 1802 following problems with contracts and payments.

The tramway was laid to a gauge of 4 feet 2 inches and the rails were set on stone sleeper blocks. The L-section, cast-iron rails were one yard long and they weighed 37 pounds each. Waggons were hauled by horses and in addition to limestone, lime and bricks, the tramway carried coal, to fire the kilns, as well as general goods.

The tramway was constructed with five notable features, a tramway bridge at Ticknall, known as ‘Ticknall Arch’ or ‘The Arch’, two smaller bridges and two tunnels. Ticknall Arch carried the tramway over the turnpike in Ticknall (Main Street, A514) and it is situated by the entrance to Calke Park. The other two bridges both lie in the woodlands of Calke Park. Calke Park Tunnel is a cut-and-cover tunnel, 138 yards long, built to take the tramway below the driveway to Calke Abbey near Ticknall Lodge. It has a variable height and width, the maximum height being about 8 feet and the maximum width being about 12 feet. The National Trust has restored this tunnel to enable visitors to walk through it. Basfords Hill Tunnel is also a cut-and-cover tunnel, 51 yards long, at Basfords Hill. It is 6 to 8 feet high by 6 feet wide and it is lined with dressed millstone grit. This tunnel has also been restored to enable visitors to walk through it.

Ticknall Tramway was in use for about 111 years, closing in 1913 and abandoned in 1915. Much of the route of this tramway can still be traced.

Tunnel House and weighbridge on the Ticknall Tramway near Ashby de la Zouch, 1913. The horse hauling a waggon loaded with limestone is about to enter Ticknall Siding at Ashby Old Parks Junction. This is a transhipment place where the stone would have been transferred to the standard gauge Derby and Ashby Branch of the Midland Railway. Beyond here the original tramway was superseded by a standard gauge line in 1874. |

In Jul 1787 he held discussions with the Erewash Canal Company concerning an extension of the canal to Pinxton but he failed to get an agreement. These discussions led to the construction of the Cromford Canal.

On the 19 Aug 1793 he produced a scheme for the Sheffield Canal. As built, this canal commenced at Sheffield Canal Basin and proceeded to by Attercliffe and Broughton Lane to Tinsley, where it joined the River Don Navigation.

In 1795 he surveyed the river Don.

In early 1796 he inspected the construction of the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal with regard to it being built as a broad canal.

On the 11 Mar 1796 he reported his scheme for a canal from the Peak Forest Canal by way of Rudyard to the Caldon Canal. This came to nothing but it did lead to the later construction of the Macclesfield Canal.

In 1799 he advised the proprietors of the Fletcher canal in the Irwell Valley on how they could best make a junction with the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal.

On the 1 Jul 1799 Outram advised the Brecon and Abergavenny Canal Company that they should convert their tramways from using edge rails to using L-section rails.

By mid-1799 he had advised the Worcester and Birmingham Canal Company that their line to Worcester should be completed with a tramway.

In mid-1800, following criticism of his first scheme, he recommends to the Somerset Coal Canal Company that the two levels of their canal should be connected by a tramway. The coal to be carried by boat in containers that could be lifted by cranes to and from waggons on the tramway.

In Oct 1800, at the suggestion of the Peak Forest Canal Company, the Huddersfield Canal Company asked him to undertake a feasibility study for a temporary tramway between Marsden and Wool Road to by pass the unfinished Standedge Tunnel. Nothing came of his study.

By Nov 1800 his double-track temporary tramway over Blisworth Hill was complete. The purpose of this was to connect the two ends of the unfinished Blisworth Tunnel.

In 1800 he produced a scheme for a tramway to run from the Monmouthshire Canal at Risca to the Tredegar Works.

By 1800 his Penydarren Tramway was complete. This was 9¾-miles long having a single track. It connected an ironworks near Merthyr to the Glamorganshire Canal at Abercynon and George Overton engineered it. On the 13 Feb 1804 this tramway witnessed a most historic moment in the development of railways for it was here that Richard Trevithick's steam locomotive first ran on rails. Samuel Homfray, an ironmaster of Penydarren then made a wager of 500 guineas even money with Anthony Hill, a neighbouring ironmaster, that a steam locomotive could haul 10 tons of iron along the tramway from Penydarren to Abercynon. On the 21 Feb 1804 Richard Trevithick won the bet for Samuel Homfray.

By 1805, after his death, The Surrey Iron Railway (engineered by Jessop) between Croydon and Reigate was complete.

All tramways designed by Outram used L-section cast-iron rails or plates, first introduced underground in circa 1787 by John Curr at the Duke of Norfolk's Sheffield Park Mine. By the following year, Curr's tramways had been constructed at two places on the surface, one of these being at Joseph Butler's Wingerworth Ironworks near Chesterfield in Derbyshire and Outram was aware of this. The cast-iron rails used were 4 feet long with a weight of 24 pounds per yard run and they were laid to a 20-inch gauge.

Their use then quickly spread to many parts of the country, both on the surface and underground, and Outram became the foremost advocate of this rail system. He referred to the rails as 'my plates' and in Feb 1801 he published his famous paper entitled, 'Minutes to be observed in the Construction of Railways'. In this paper he recommended that the gauge should be 4 feet 2 inches and the Peak Forest Tramway, which opened for trade on the 31 Aug 1796, was the first to be completed fully in accordance with his subsequent paper.

For Benjamin Outram's paper click here » Minutes

In 1801 Outram took less interest in his private civil engineering consultancy practice and he devoted himself more to the business affairs of Benjamin Outram & Company. He did this with the aid of his brother, Joseph, and his managing clerk, George Goodwin. The reason for this was the firm's rapid growth.

Outram died prematurely on the 22 May 1805. The firm of Benjamin Outram & Company was formally established by a deed of partnership dated 10 Dec 1792 and in 1809 the name was changed to The Butterley Company. However, Benjamin Outram lived long enough to see his firm become one of the foremost ironworks in Britain, both with regard to the quality of its products and its output. Ultimately, the company became one of the largest and most prestigious ironworks in Britain, specialising in structural steelwork and railway equipment.

Benjamin Outram was naturally gifted and one of the earliest references to him in a consultancy role was in Jul 1787 (aged 23 years) when, accompanied by John Hodgkinson and others, he held discussions with the Erewash Canal Company to propose an extension of their canal to Pinxton. Although nothing came of this, it led to the construction of the Cromford Canal. Two years later, in 1789, he was appointed as the full-time assistant to William Jessop. John Smeaton had trained Jessop and he was a member of the Smeatonian Society. Between 1785 and 1805, Jessop was the premier civil engineer of the day and Outram could not have had a better mentor. In 1793 (aged 29 years) he was appointed as the Consulting Engineer to the Nutbrook Canal Company and it is likely that this was his first appointment as a consultant. The Nutbrook Canal was completed without any problems.

It had become incumbent on civil engineers of the day that they must understand the underlying mathematical principles of the design of arches and buttresses as these were common features of bridges, aqueducts and tunnels. In this respect it was crucial for them to recognise the importance of the work of the mathematician Charles Hutton (1737-1823). For civil engineers, the two most important works of Hutton were his 'Principles of Bridges' (1772) and 'Mathematical Tables' (1785).

It is understood that both Benjamin Outram and Thomas Brown consulted the former publication at the design stage of Marple Aqueduct and the latter publication would have been of use to them as an aid to their calculations. The University of Salford holds an original copy of the 'Principles of Bridges'.

It is also interesting to note that the second eldest son of Benjamin Outram was called James Napier Outram. It is possible that his middle name, Napier, was given in honour of the Scottish philosopher and mathematician, John Napier (1550-1617), who was the inventor of the decimal point and of logarithms. This is especially so knowing that there was an influential Scottish connection in Outram's family.

Benjamin Outram was born at Alfreton, near Matlock, Derbyshire, on the 1 Apr 1764 and he was baptised on the same day. He was named in honour of Benjamin Franklin, the American printer, scientist, inventor and politician who was a personal friend of the Outram family. Besides his well-known experiments with electricity, Franklin was also the inventor of the glass harmonica, which has such an enchanting sound, especially when playing Scottish airs.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) came to live in England in 1757 and he was Benjamin Outram's godfather. While in England, Franklin was a Colonial representative of his home state of Pennsylvania and of Georgia, New Jersey and Massachusetts as well.

Benjamin Outram was the second son of Joseph Outram (an iron master and surveyor) and Elizabeth and the grandson of Joseph Outram and Sara. He married Margaret Anderson the daughter of James Anderson (a Scottish lawyer, scientist, agriculturalist and writer) and [?] Seton on the 4 Jun 1800. In the short time that they were married they had five children, Francis Boyd, Anna Seton, James Napier, Margaret and Elizabeth.

He worked prodigiously all his life but in spite of this he still owed his business partnership a substantial sum of money at the time of his death. He had a rather extravagant life style and he spent some thousands of pounds on improving Butterley Hall where he lived. In a letter of 1805 he was described as 'a fine looking, high spirited man, of a generous temper and a relentless energy which would ill brook opposition'.

Tragically, Benjamin Outram died prematurely of brain fever in London on the 22 May 1805, aged 41 years. As his second son, James Napier, was born on the 22 Feb 1803 and he would scarcely have been able to remember his father. James went on to have a distinguished career in the British Army, rising to the rank of Lieutenant General, his full title being Lieutenant General Sir James Outram, 1st Baronet, but he was also well known by his nickname of the Bayard of India (Bayard being a French military hero). While serving in India he was involved with the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. He died on the 11 Mar 1863 at Lucknow, aged 60 years. Benjamin's widow, Margaret, died on the 7 Jan 1863, aged 84 years, at 8 Forrest Street, Edinburgh, and she was described as the widow of Benjamin Outram, a Civil Engineer.