Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (14 Nov 1765-24 Feb 1815) was born in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and he came to England in 1786. He lived in Philadelphia for a while and it is said that it was

here that he was apprenticed to a silversmith for a while but there is no evidence to confirm this. However, he was a miniature and portrait painter and an engineer who came to England ostensibly to study painting.

Here he met the Duke of Bridgewater, whose canal was shortly to be used for trials of a steam tug and who subsequently ordered a number from William Symington. Fulton is widely credited with the development of

the first steam-powered boat, although this is not strictly accurate. In 1796 he published his most famous work entitled, 'A treatise on the improvement of canal navigation'.

This treatise contained designs for aqueducts (including iron aqueducts), inclined planes, boat lifts and canal boats. He was a man ahead of his time because the technology of the day was not compatible with his ideas.

Robert Fulton (14 Nov 1765-24 Feb 1815) was born in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and he came to England in 1786. He lived in Philadelphia for a while and it is said that it was

here that he was apprenticed to a silversmith for a while but there is no evidence to confirm this. However, he was a miniature and portrait painter and an engineer who came to England ostensibly to study painting.

Here he met the Duke of Bridgewater, whose canal was shortly to be used for trials of a steam tug and who subsequently ordered a number from William Symington. Fulton is widely credited with the development of

the first steam-powered boat, although this is not strictly accurate. In 1796 he published his most famous work entitled, 'A treatise on the improvement of canal navigation'.

This treatise contained designs for aqueducts (including iron aqueducts), inclined planes, boat lifts and canal boats. He was a man ahead of his time because the technology of the day was not compatible with his ideas.

Charles McNiven

Charles McNiven was possibly born at Forgandenny, Perth, Scotland, on the 8 Mar 1759, to John McNiven and Anne Young and he was baptised on the 11 Mar 1759.

By 1788 he was in business in Manchester with premises on Alport St (now the northern end of Deansgate), where he described himself as an architect and designer. By 1800 he had moved to 66 Bridgewater St. He served on the Committee of the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal between 1791 and 1814 and he surveyed the line for this canal. In 1793, with others, he made a preliminary survey of the Haslingdon Canal, which was to be a tub-boat canal much favoured by his business partner, Robert Fulton. In the event, this canal was never built. In the same year he surveyed the Old Navigation (Mersey and Irwell Navigation) with respect to improving its efficiency. In connection with this work, it is believed that he was the engineer for the construction of the Runcorn and Latchford Canal, which was completed in 1803. In Sep 1804 he wrote to Liverpool Corporation advising them of the advantage of the Rochdale Canal, although it was not fully open at the time.

The association of Robert Fulton and Charles McNiven with the Peak Forest Canal Company

It seems that it was in Oct 1794 that Charles McNiven and Robert Fulton made their appearance on the Peak Forest Canal.

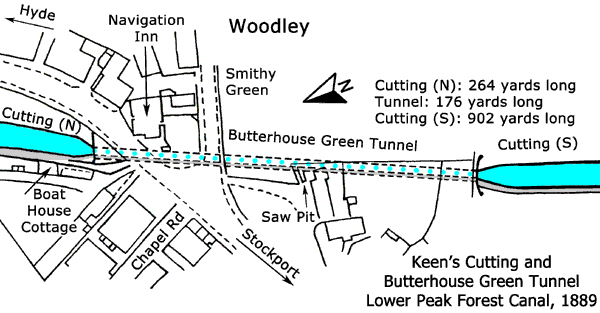

The two men had formed a short-lived partnership as contractors and the Committee of the Peak Forest Canal Company awarded them with a contract to cut a section of the canal in the Woodley area at a place that was to become known as Keen's Cutting. This section of the canal included Butterhouse Green Tunnel but whether or not this contract included boring the tunnel is unknown but the possibility cannot be disregarded.

Events did not go well for Messrs McNiven and Fulton and Benjamin Outram, the Consulting Engineer, reported to the Committee that

Messrs Fulton and McNiven are not proceeding in the cutting of the said part of the canal contracted to be cut by them.

This observation by Outram was recorded in the Minute Book of the Peak Forest Canal Company on the 4 Mar 1795. This lack of progress was not, perhaps, surprising when taking into consideration McNiven's engineering commitments on other canals in the Manchester area and Fulton's bid to cut a section of the Gloucester and Berkeley Canal. His bid for a contract was recorded in the Minute Book of the Gloucester and Berkeley Canal Company on the 3 Feb 1795. In the event, this bid was unsuccessful but it must have taken him away from his work on the Peak Forest Canal.

Charles McNiven withdrew from the contract to leave Fulton on his own and then he withdrew to be replaced by another contractor whose name is unknown. He too withdrew leaving Thomas Brown, the Resident Engineer, to carry the excavation through to completion and stabilisation of the cutting sides with stakes, mats and grass clods all firmly consolidated.

Considering that Benjamin Outram was the Consulting Engineer to the Peak Forest Canal Company, Fulton's next move, before departing from the scene, was astonishing, for he began to give advice to the Committee of the Peak Forest Canal Company on engineering matters and, surprisingly, they seemed to have listened to what he had to say and liked what they heard. Outram's outrage at this turn of events can easily be imagined.

From the outset, it was intended that Marple Aqueduct was to be built of stone to a joint design by Benjamin Outram and Thomas Brown, the Resident Engineer. The contract for its construction was placed with Messrs William Broadhead, Bethel Furness and William Anderson and this was signed on the 5 Feb 1795. Regardless of this, the Committee resolved on the 22 Apr 1795,

····· that Mr Fulton's Idea of substituting Cast Iron instead of Stone Arches for the Aqueduct over the River Mersey (now the River Goyt) is approved, and that the Engineer (Benjamin Outram) and Mr Fulton be desired to give the (Company) Clerks instructions for particulars of an Advertisement for procuring Offers of Terms for furnishing Cast Iron for making the same.

Fulton's advice to the Committee did not stop at this revolutionary change to the plans already drawn up. He went on to advise the Committee not to build the proposed locks at Marple but, instead, to build an inclined plane, over which tub-boats would be carried travelling in special cradles running on rails. After listening to this advice, the Committee instructed Outram on the 23 Apr 1795, along with two others,

to view the operation of Small Boats and inclined planes at Coalbrook Dale and to report the result.

On their return, the three observers reported that small boats (tub-boats) and inclined planes would be practical, and would save money.

At this juncture, the Committee delayed making their decision on this matter but on the 18 May 1895 they

resolved that Mr Fulton be requested to print his Ideas of the comparative Advantages of twenty Ton Boats and five Ton Boats with Two Ton Boats and Railways and that Mr Fulton do get 200 Copies thereof printed at the Expense of the said Company.

This request to commit his ideas to paper may firstly have become the article he wrote about 'Small Canals' that was published in the London Morning Star on the 30 Jul 1795 and then in his book, A Treatise on the improvement of Canal Navigation, which he published in 1796. It is not known who paid for the publication of his Treatise but it is strongly suspected that the Peak Forest Canal Company paid for it.

On the 3 Jun 1795, the Committee voted Fulton 100 guineas for

having suggested to the Committee ···· many Ideas in and about the execution of the said Canal and its works and drawn and produced to this Committee many plans.

The Minute Book entry for the 11 Sep 1795 shows that Robert Fulton was still working for the Canal Company, as a contractor, but this was to be his final mention. His sudden disappearance from the affairs of the Peak Forest Canal Company is an unresolved mystery but his removal must have come as a relief to Benjamin Outram.

Subsequently, Marple Aqueduct was completed in stone, as originally planned, and Marple Locks were opened throughout in Nov 1805. There was no more talk of inclined planes and tub-boats, although there is evidence that a small number of tub-boats may actually have been built. On the 2 Mar 1796 the Minute Book records that

the Engineer to have built six 20-25 ton Trading Boats and so many small Boats to be made as with those already made and making will make ten.

The small boats referred to here may have been similar in design to tub-boats but it is likely that these were needed for canal construction and maintenance purposes and not for trading. Indeed, the entry clearly distinguishes them from trading boats.

Nonetheless, Fulton's sudden disappearance may not have been quite the end of his sway over the Committee. On the 21 Mar 1806, James Meadows Senior, the Company's Agent, reported that the paddles of the locks at Marple were not working properly and that they could be repaired over two or three weeks for £400 (that is, £25 per lock). It is understood that when the locks first opened that innovative paddle gear, using compressed air, may have been fitted and that this had to be replaced by conventional rack and pinion paddles because it was a failure. If the locks were, indeed, fitted with some type of pneumatically operated paddles then this suggests that Robert Fulton may have been responsible for their design. His ideas were so far ahead of the technology of the day that they could not be implemented.

South portal of Butterhouse Green Tunnel, 1930s.

The tunnel is seen here from Keen's cutting. This 176yd-long tunnel has a towpath through it but boats cannot pass inside it.

South portal of Butterhouse Green Tunnel, Feb 2006.

The tunnel is seen here from the same vantage point as the picture to the left.

North portal of Butterhouse Green Tunnel, Feb 2006.

It is interesting to note that Fulton's visits to Britain and France occurred during the Napoleonic War and it seemed to be a feature of the time that commercial interests did not let the war get in their way.

Epilogue

Fulton died in the USA and he is buried in Trinity Churchyard Cemetery, Manhattan, New York, and Fulton County, Ohio, is named after him.