Bow Garret, Two Trees Ln, Haughton Green

This was a small two-storey brick built structure with one room on each storey and a single-storey extension attached to one gable end. The garret was used for bowing fur while the ground-floor room and extension

were used as planking shops.

The premises originally belonged to Samuel Warburton and records show that in 1832 he bequeathed them to his son-in-law, Samuel Arrandale. Both men were described as hatters. The same records also provide the names of three other hatters, Thomas Andrew, Adam Holland and George Ward. The 1841 census shows that Adam Holland (aged 30, a journeyman hatter) was living on Two Trees Ln with his father, George Holland (aged 70, a journeyman hatter), and younger brother, George Holland (aged 15, an apprentice hatter), as well as other members of the family. In 1851, Adam Holland was still living on Two Trees Ln with his wife and family where he was a hat finisher.

The premises were situated behind terraced houses on the north side of Two Trees Ln, a short distance from the Chapel House Inn. Formerly they adjoined Taylor’s Square and Moorfield Farm.

Bow Garret

Typically, a bow garret took the form of a small two-storey brick built structure with one room on each storey (‘one-up-and-one-down’). The word ‘garret’ is defined as a room at the top of a building

just below the roof.

There was a hearth on the ground floor and a large workbench in the garret. The name 'bow garret' originated from the first stage of manufacturing hats, where fur was prepared ready for it to be turned into felt, and this was done in the garret. This process was called 'bowing' and it consisted of fur being separated with a 'hatter’s bow'. This was a large wooden implement consisting of a pole made of ash strung with catgut attached between a bridge at either end of the pole. A hatter’s bow had a passing likeness to a violin bow.

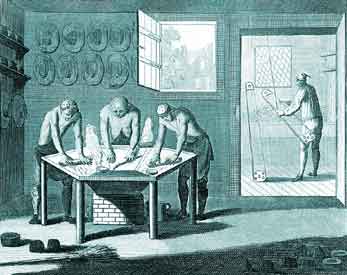

The loose fur was first spread out over the bench and then the string of the bow was plucked with a wooden pin that caused it to vibrate. The bow string was then passed through the fur causing it to fly up in the air and then settle evenly on the bench. The separated fur was then formed into a roughly triangular shape, called a 'bat', and then pressed and matted together either by hand or with a piece of woven willow (osier) called a 'gathering basket'. Two bats were then taken and laid on top of each other, separated by a piece of damp cloth or leather. Two edges of each bat were then teased together, thus joining them to form a cone-shaped hood. This hood was then ready for the second stage of hat manufacture, which was 'planking'.

Planking was done on the ground floor and this was where the material was turned into felt and eventually into an unfinished hood in the basic shape of a hat. The planking process took place on the ground floor because it required hot water contained in a large open vessel called a 'kettle', the hearth being used to heat water. To do this the hood was alternately dipped in a solution of hot water, sulphuric acid and mercurous nitrate and then rolled on a plank with a planking pin (aka a hatter's pin).

Left: An illustration of 'planking' in the front room and 'bowing' in the back room, c.1750.

Right: An illustration of 'bowing', early 19th century.

Hatter's bow.

A surviving bow garret is situated in the grounds of a house on Market St, Denton. It is listed as a domestic hatting workshop, Grade II, List Entry No. 1419033. The bow garret was on the first floor and a planking workshop was on the ground floor.

Further Reading

Nevell, Michael with Grimsditch, Brian and Hradil Ivan, 2007. Denton and the Archaeology of the Hatting Industry. Vol. 7 in the Archaeology of Tameside Series. Loughborough, Leicestershire: Q3 Digital/Litho.